Understanding Comics Analysis

Analyzing an analysis itself is quite the challenge, I found, as I was reading this and trying to find which part in particular I would talk about. What I ended up arriving on was found on pages 24-59, in Chapter Two, The Vocabulary of Comics. I chose this chapter because of it's interesting takes on not only comics, art and writing, but because of it's involvement in psychology as well. I have always taken a personal interest in psychology, and seeing a medium I love being combined with it was an offer I couldn't pass up.

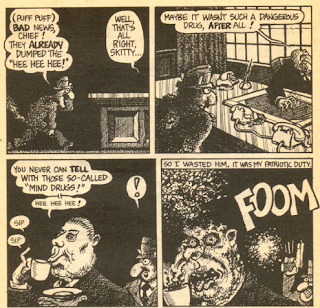

The focus of this chapter is on "The Icon" (or symbol) as it's used in the art world, meaning drawings that represent real life people or objects. He discusses how human beings have always, and will continue to, imprint themselves on sentient objects, and how this transfers over to the world of comics/cartooning. We, as a species, can't help but want to imprint humanity on things that don't have it, and he demonstrates this with the very simple shape of a circle, two dots and a line that forms a straight faced icon. He even makes the point of his own representation being nothing more than a learning tool--an empty shell meant for us to see past.

These are all well documented facts in the field of psychology, and his understanding and application of them was exemplary. The use of seemingly "simple" designs/characters is used widely across all creative fields (simply look at the "silent protagonist" in many video games/movies for that) and beside it much more time efficient to draw people more simplistically, it's also beneficial to our self centered human minds. It engages us more. And who among us hasn't picked a favorite character in a media because they remind us of ourselves? Because we identify we them the most?

This is not to say more realistic designs don't have their place. McCloud says later in the chapter about how the Japanese in particular have taken the idea of over-detailing something to other it from ourselves completely, to objectify it. (Something like JoJo's Bizarre Adventure comes to mind) This makes storytelling just as easy as simplistic, identifiable faces because we aren't so concerned with projecting onto a character, but instead seeing what they're doing. There's even a place for the top of the pyramid on pages 52-53, where you can become truly story-driven because your visuals are so abstract to the point of being only shapes.

(An unrelated example being the video game Thomas is Alone, a fantastic platforming game who's main characters are nothing but various colored squares and cubes with different abilities. The narration and way the cubes abilities work together is the only characterization you receive yet it is a deeply character driven experience.)

So in the end, all corners of the triangle have their place. There is no uncanny valley, as there tends to be in life, because any style can serve to tell any story if the to are wed enough. If they work towards the same purpose, and have a deep understanding of what their comics and style choices mean. If they Understand Comics.

The focus of this chapter is on "The Icon" (or symbol) as it's used in the art world, meaning drawings that represent real life people or objects. He discusses how human beings have always, and will continue to, imprint themselves on sentient objects, and how this transfers over to the world of comics/cartooning. We, as a species, can't help but want to imprint humanity on things that don't have it, and he demonstrates this with the very simple shape of a circle, two dots and a line that forms a straight faced icon. He even makes the point of his own representation being nothing more than a learning tool--an empty shell meant for us to see past.

These are all well documented facts in the field of psychology, and his understanding and application of them was exemplary. The use of seemingly "simple" designs/characters is used widely across all creative fields (simply look at the "silent protagonist" in many video games/movies for that) and beside it much more time efficient to draw people more simplistically, it's also beneficial to our self centered human minds. It engages us more. And who among us hasn't picked a favorite character in a media because they remind us of ourselves? Because we identify we them the most?

This is not to say more realistic designs don't have their place. McCloud says later in the chapter about how the Japanese in particular have taken the idea of over-detailing something to other it from ourselves completely, to objectify it. (Something like JoJo's Bizarre Adventure comes to mind) This makes storytelling just as easy as simplistic, identifiable faces because we aren't so concerned with projecting onto a character, but instead seeing what they're doing. There's even a place for the top of the pyramid on pages 52-53, where you can become truly story-driven because your visuals are so abstract to the point of being only shapes.

(An unrelated example being the video game Thomas is Alone, a fantastic platforming game who's main characters are nothing but various colored squares and cubes with different abilities. The narration and way the cubes abilities work together is the only characterization you receive yet it is a deeply character driven experience.)

So in the end, all corners of the triangle have their place. There is no uncanny valley, as there tends to be in life, because any style can serve to tell any story if the to are wed enough. If they work towards the same purpose, and have a deep understanding of what their comics and style choices mean. If they Understand Comics.

Comments

Post a Comment